1869 Harper's New Monthly Magazine - The Helderbergs

In 1869, Harper's New Monthly Magazine published a 16 page article on The Helderbergs. Future write-ups on the Helderbergs often borrow information from the article.

HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE - Click HERE to see original pages.

THE HELDERBERGS

IN the State of New York are three principal mountain chains. The Adirondacks cover the northern, granite region of the State, of rock which has been violently heated, if not melted, by the earth's internal fires. They are igneous, plutonic mountains, with peaks perhaps six thousand feet above tide-level. The Catskills are an isolated group of peaks on the Hudson, more than a hundred miles south of their granite elder brethren of the Adirondack. They are principally of the old red sandstones and shales which underlie the coal formation. These are sedimentary rocks, the silt of ancient ocean currents; their peaks exceed three thousand feet in height.

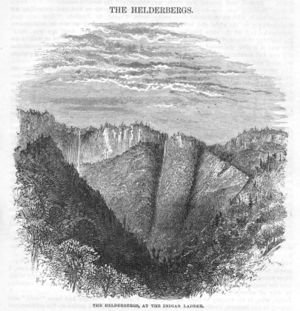

Between these, north of the Catskills, not twenty miles distant, is a line of small mount¬ains known as the Helderbergs, the third though not the least of the mountain systems of New York. They are a long angular range of solid blue limestone cliffs, running nearly east and west. Their geographical name exists only in Albany County; but, geologically, they are over three hundred miles in length, their unbroken strata reaching from the Hudson to Niagara and on into Canada. Their greatest altitude is one thousand two hundred feet.

These calcareous cliffs, filled with fossil, petrified sea-shells, answer to the European Silurian and Devonian ages. By its peculiar fos¬sil shells the Helderberg, like other rock, is known when met with in distant regions. In subterranean darkness it stretches, a hidden, undulating sheet of strata, an inner mantle to the continent, cropping out here and there, and leaving its wooded "Silurian ruins" to render picturesque the scenery of many a State.

In the far West a geologist picks up a fossil shell, examines it, and says, " Helderberg"- surmises that good limestone may thereabout be found, and gypsum for the plasterer's art, and iron pyrites - fool's gold-useful for sulphur and sulphuric acid manufacture. Caves also may be expected, and sulphur springs, strontian, or barytes, if not more valuable deposits, may be near.

A Tennessee geologist also picks up a petrifaction, and makes note of it as "Helderberg." In Britain Sir Roderick Murchison, mentioning the existence of his favorite Siluria in America, will not fail to speak of the Helderberg formation. Yet it is possible that of these three not one had ever seen the Helderberg.

"Helderberg" is a Dutch corruption of the old German Helle-berg, meaning "Clear Mountain." This name was given by the first settlers of Schoharie County, who had the bold and distinct berg constantly in view during their first day's journey - westward into the then wilder¬ness. Though plainly visible, and but ten or fifteen miles from the ancient city of Albany, few of its citizens appear even to know of their existence, let alone their traditions and their beauties. Helderberg to many Albanians means `anti-rent," "sheriff's posse," military, blue uniforms, bright muskets and bayonets, and shackled prisoners, against whom no crime being proved they are always released.

Most of the farms on these hills were what was once called "manor land." It had its feudal lord and manor-house after the fashion in England prior to our Revolution. The farm¬ers were peasantry, of whom feudal rents in the shape of wheat, chickens, and "days' service" were exacted, though the land was indentured, or deeded, to them, their heirs and assigns for¬ever. Ignorant emigrants were led to purchase, invest their all, clear and improve the land, and give it value, not dreaming that they would have to pay the interest on their own improvements. Alas ! they found that they had exchanged the hard lot of a Holland "boor" for one even hard¬er. Shrewd Yankees, living on free soil, jeered at them as slaves.

The Revolution came, the battles of liberty were fought, and down went Tory and Royalist. After that feudal exactions seemed hard and oppressive, as well as unrepublican and monarchical. Some now refused to pay the "quarter sale" - one quarter of the price received by the farmer each time a place was sold. If the farm was sold four times the "Lord" received the cash value of the farm, and still pretended to own it! Threats not sufficing, they were called "Anti-renters," and war was levied upon them. But since then the conflict has raged, nor is it ended yet; but quarter sales are abolished.

The Susquehanna Railroad trains, as they leave Albany crowded with tourists bound for Sharon Springs, the beauteous Susquehanna Riv¬er Valley, or distant Pennsylvania, are forced to follow the wall-like precipices facing the Helderberg almost along their whole extent, far to the north and west, before they are able to climb it. It is its romantic wooded rock scenery, dark caverns, and sprayey waterfalls, its varied landscape and accessible mountain grandeur, that render the Helderberg interesting to artist, author, poet, tourist, or rusticator.

The traditions herein written are at least as true as traditions ever are, and I tell them substantially as they were told to me. The sketch¬es may give some idea of the scenery.

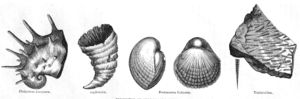

To those who desire to escape for a day from the oven-like city in summer; who wish to en-joy a scramble among romantic cliffs, in shady woods, beside cool mountain brooks and waterfalls; to view spots sacred to legends of wild Revolutionary days, of Tory and Indian depredation, naming place, precipice, and mountain; to gather the fossil corals and shells (univalves, bivalves, and brachipods) which, forming the very soil the farmer tills, cropping from out the sod, are reared as farm walls or burned to lime; to visit and explore known caves, and search for new ones, possibly existing unknown and unexplored, among the cliff ledges, the "Indian Ladder" region of the Helderbergs offers superior inducements.

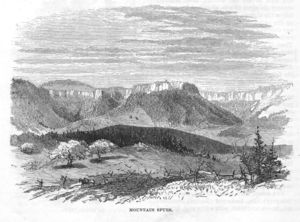

Taking an early train on the Susquehanna Railroad and stopping at Guilderland Station brings one within a mile of the Indian Ladder Gap. Even from that distance the mountain spurs are visible. Wondrous are the deep, black shadows that they cast early in the day. A scarcely discernible zigzag ascending line, not unresembling a military-siege-approach, shows the Indian Ladder Road crawling up the mountain and along and beneath the precipices.

It is but an easy two hours' drive, however, from Albany, and many may prefer to visit it in the saddle or with a pleasant party. If the weather be dry and not very sultry the jaunt will well repay you. If your horses are brave and steady you may drive up the mountain road - it is a mile to the summit - or you may lead your horses up, the party walking leisure¬ly after. Still some descending team may be met, and it is ill passing on that narrow cliff road. Notwithstanding many accidents this road is the highway, winter and summer, of the country folk.

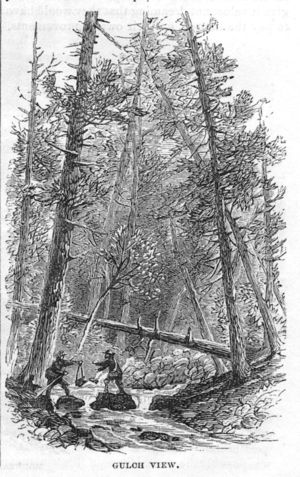

If, however, you have a desire to "foot it," and wish to see the wildest, most romantic scenery the place affords, abandon the road and follow the stream, called by some Black Creek, up the valley to the foot of the gorge - a sav¬age stairway up the mountain slope, of broken rock-fragments and great water-worn boulders. Then, if your heart fail you not for any place more difficult to climb is impassable – you will ascend for a breathless, dangerous, exciting three or four hours to the foot of the cliffs and the falls – an escalade which will bear compari¬son with any thing climbable.

But you should not return without mementoes of your visit. Carry then a satchel, unless you have capacious pockets for curiosities will meet you on every side. Besides the fossil medals of creation-petrifactions and minerals - the collector will find a thousand objects of interest. If he have keen eyes he may note some curious grafts, great hemlocks on huge pine-trees, perhaps of Indian handicraft. Large slow-worms, unknown lizards, insects, perhaps black - snakes, toads, and eels, mingled in strange confusion, swarm amidst the rocks. The place was once renowned for the multitude, size, and venom of its rattlesnakes.

The damp, thick woods of oak, hickory, red (slippery) elm, basswood (linden), butternut, ash, beech, and birch, with white pine, hemlock, and some spruce, give color to the scenery, heightened by the green, graceful frondage of the scarlet-fruited sumac, the trailing cordage of the wild grape-vines, and the numberless other rarer wild plants-annuals, biennials, perennials, every where luxuriant.

Your satchel may contain some luncheon; a geological hammer and a chisel would not be inappropriate; your sketch-book by all means. Gun or fishing-tackle here are useless; hunting there is none save foxes, "coons," some ruffled grouse (partridge), and at times wild pigeons. The fishing is also poor, except for pickerel, perch, sunfish, and the like, in lakes and brooks amidst the hills back from the sum¬mit.

What is this Indian Ladder so often mentioned? In 1710 this Helderberg region was a wilderness; nay, all westward of the Hudson River settlements was unknown. Albany was a frontier town, a trading post, a place where annuities were paid, and blankets exchanged with Indians for beaver pelts. From Albany over the sand plains - Schen-ec-ta-da (pine¬-barrens) of the Indians-led an Indian trail westward. Straight as the wild bee or the crow the wild Indian made his course from the white man's settlement to his own home in the beauteous Schoharie Valley. The stern cliffs of these hills opposed his progress; his hatchet fells a tree against them, the stumps of the branches which he trimmed away formed the rounds of the Indian Ladder.

That Indian trail, then, led up this valley, up yonder mountain slope, to a cave now known as the "Tory House." The cave gained that name during the Revolution: of that more anon. The trail ended in a corner of the cliffs where the precipice did not exceed 20 feet in height. Here stood the tree-the old Ladder. In 1820 this ancient ladder was yet in daily use. There are one or two yet living who have climbed it. Greater convenience became necessary, and the road was constructed during the next summer. It followed the old trail up the mountain. The ladder was torn away, and a passage through the cliffs blasted for the roadway. The rock-walled pass at the head of the road is where the Indian Ladder stood. The Indians had once a similar ladder near Niagara Falls. There were probably many such among the cliffs. It was possibly the resemblance of this wild mountain scenery to that of father-land far away that induced its early settlement by the Swiss, and gave the name of Berne to the neighboring town.

You have followed the rapid brook up the valley through the shadowy woods, and have reached a little prairie-an opening surrounded almost on every side by the great mountain slopes which rise grandly to the impregnable cliffs walling the summits. It seems a window whereby the crag - climber may observe the whole extent of his labors. This spot was known as the "Tory Hook" or Plat, and in days gone by was their rendezvous-a lone, sequestered glade of the savage forest. Above you, in front and to right and left, is a colossal natural amphitheatre, the long, wooded slopes rising tier on tier to the base of the circling precipices. Two rocky gorges, which ascend like the diverging aisles of an amphitheatre, part the wilderness of green. The steep slopes have four-fifths of the mountain height.

Towering above the uppermost tree-tops are the gray, battlement-like cliffs. Many a dark opening, gloomy recess, and inaccessible ledge can be seen which human foot has never trod; once, probably, the pathway and home of that blood-thirsty savage, the nimble and stealthy - footed cougar. Two lofty waterfalls stream down, milk-white, from the cliff-top at the head of each dry, rock-filled gorge. Your way lies to the right, up the gorge to the smaller of the two falls.

Following the stream and entering the opposite woods you commence the ascent of the gorge. It is no light undertaking. The bed of the stream is your best road; keep to the right. Difficulties begin; you are frequently compelled to cross the rapid stream on stepping¬stones. At length you reach what may be termed the foot of the gorge. The stream rushes down in a number of little cascades - above it is lost amidst the huge rocks. Look upward, your labor lies before you.

Up, then ! Up ! All is fatiguing ? Look below! It seems easier to climb up than down. Retreat appears impossible, if not recreant. Upward, then! no longer over fallen rocks merely, but over prostrate cliffs rather. Huge blocks as large as little cottages or backwoods log-cabins are heaped in wild confusion; up them and over them! More toilsome, nay, dangerous, becomes the ascent; but now the novelty and danger give new zest, and "Forward !" shouts one. Whereat you all, with vigorous competition hurrying, climb and scramble up¬ward; sometimes on foot, oftener upon hands and knees, and frequently prone, with aid of fingers and toe of boot making slow progress up the face of some fallen mountain.

To climb, some aid themselves with sticks snatched up from where they were cast by the last great freshet that foamed down the wild gorge. The barkless pole, dry and withered, often fails the user, who scarce has time to drop the worthless fragments, snatch a firm grip upon immovable rock, and thank his stars that he has not followed the fragments of his staff that rattle down half a hundred feet before they reach a cranny large enough to hold them. Do not take each wriggling thing among the rocks to be a snake. Once thinking to capture what I took to be a serpent sunning himself on the rocks, I found I had a sleek, fat eel! An eel there on those dry rocks? Assuredly. For, hark! do you hear that steady rushing sound, as of a subterranean waterfall? Hours of toilsome climbing have passed. Look upward, the falls are before you at last.

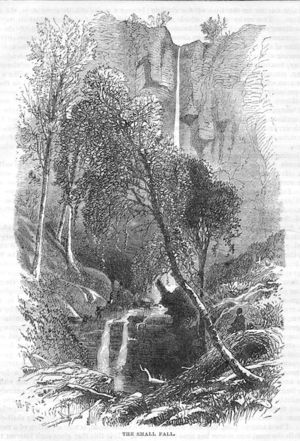

From the brink of the dark cliff drops a spray-white stream, about eighty feet, unbroken. Lost for a moment to sight it issues from a rocky basin, and ripples down in two streams brightly over a series Of little stone steps, the angular parallel edges of abraded schist strata, seldom over an inch in thickness. Suddenly the smooth descent ceases; the rock drops perpendicularly fifteen or eighteen feet. Down the face of this wall or "fault" dash two little cascades; they fall upon another series of the miniature rock steps, and, glittering and shining like a magic stream of crystal, hurry down to lose their waters among the huge rocks of the gorge; lost for a thousand feet of that dread mountain slope ere coming forth to light again as the stream in the valley below. At last beneath the precipice you stand in the cool shadow of the dark dripping rocks, at the foot of the falls, the top of the gorge - that goal for which you have so arduously labored.

This is the Small Fall, sometimes called the "Dry Falls." The latter name you will hardly appreciate should you visit it when swollen by recent rains. Here you may enjoy an un-equaled shower-bath; but the stream carries pebbles, and the dashing water itself stings like a shower of shot.

Below (and on the cliffs above) this fall is one of the best localities for Helderberg fossils or petrifactions. Among these fossil shells of ancient seas are many peculiar to the Helderbergs. The names and features of these shells once mastered, two of the most important of geological ages are known to you. On the Pacific slope, amidst the Sierras, throughout the North American continent, even in foreign lands, knowing these fossils you will be able to recognize the Silurian and Devonian rocks. The Helderbergs are principally Silurian; above this, on the summit of the hills and on their southern slopes, Devonian rocks are found.

When, years ago, Lyell in his geological travels visited these hills, he was struck with amazement. It seemed a new, a forgotten world. There is a stratum of the cliff rock, sometimes fifty feet in thickness, entirely com¬posed of one variety of fossil shell - the Pentamerus galeatus-the shells massed together in a way astounding. This, once the shell-covered bed of an ocean, is now a portion of a mountain cliff. It is this that gives such interest to Helderberg precipices, more than to basalt Palisades, or even dread Wall-Face of the Adirondacks.

If you are fortunate you may find the out¬crop of that stratum and bring away a "chunk" of shells. Besides the Pentamerus a dozen or more varieties of fossils may here be found. Spirifer and Athyris, whose delicate internal spirals art has brought to light. The well- named Platyceras dumosum, a flat horn covered with spikes, as its name implies. The beautiful minute Tentaculites, that resemble little pet¬rified minnows or fishes just hatched - they fair¬ly swarm on the thin, clinking fragments of the water-lime stone. Encrinoids (stone lilies), ancient Trilobites (dalmania), with their num¬berless eyes, perhaps a rare, odd-looking thing called. a Cystad, a beautiful little Euomphalus, a butterfly-like Strophomena, an Atrypa or Rynchonella, cornucopia-like Zaphrentis - Corals (favorites), Bryozoans, Fucoids, and others valuable to the geologist, surprising and interest¬ing to any one.

These rocks (or rather the rocks of this age) were till within a year called Pakaeozoic, as containing "the most ancient life." Fossils have since been found in the older, granite Azoic (without life) rock. Those names, having lost their meaning, are now obsolete.

Vol. XXXIX.-No. 233.-42

Along beneath the cliffs runs a narrow path. The debris of the mountain drops on one side (a steep wooded slope); on the other the over¬hanging precipice forms a wall. Westward this path leads to the Indian Ladder road; and, going that way, you pass a curious spring. At the base of the cliff is a dark opening, about three feet high by six or eight in width, narrow¬ing inward. From the dark interior of the cliff a clear, sparkling stream issues, constant summer and winter. This place I once explored in a boat built for the purpose, narrow and coffin-like, carried thither from the road along the ledges. I found a black, narrow passage - no deep water, lakes, or large rooms - nothing to reward me for my pains.

Eastward the path leads to the "Big," "Mine Lot," or "Indian Ladder Falls." Have a care when following this path; the overhanging rocks are often loose and trembling. Sometimes your mere approaching tramp will be sufficient to cause their rattling fall. Suddenly you turn a corner of the cliff, and pause in admiration of the scene before you.

From the edge of the overhanging precipice, more than a hundred feet above your head, streams down a silvery rope of spray, with a whispering rush, sweeping before it damp, chilly eddies of fugitive air, that sway the watery cable to and fro. Back, beneath the rocky shelf from off which the fall precipitates its unceasing stream, is a black, cavernous semi-circle of rock, its gloomy darkness in deep contrast with the snow-white fall. Below, to the left, the woods are swept away to the base of the mountains, and in their place a wild and desolate descent of broken rocks falls sharply-rendered more savage to the eye by the shattered trunks of dead trees mingled.

Back of the fall at the base of the precipice is a low, horizontal cavity in the rock, from four to six feet in height, fifty or sixty feet in length, by fifteen in depth. Stooping and clambering in over a low heap of rubbish probably the old waste of the mine you enter. Mine, strictly, there is none; but the marks of mining implements and the excavation show that operations of some kind have been carried on. Here is a massive vein of iron pyrites (bisulphide of iron), fine-grained and solid, and well suited for sulphuric acid manufacture. The bed or vein of pyrites has evidently been much thicker, but it has decomposed, a yellow oxyd of iron and sulphate of lime (gypsum) resulting.

The particular appearance of the bed is interesting. At the bottom of the excavation can be seen the glittering masses of pyrites, above them calcareous incrustations, over which ap-pears the yellow oxyd of iron, resulting from the decomposition of former pyrites, seamed and segregated with veins of gypsum - misnamed "plaster of Paris." There is no sulphate of iron (proper) or green copperas resulting, but a white, acid, crumbling substance answering to Coquimbite (white copperas) may be found and a yellow incrustation, in one place at least, resembling sulphur flowers. The oxydized sulphur of the pyrites, as sulphuric acid, has united with the limestones to form the gypsum, of which there are sufficient indications to warrant a search. As the limestones are frequently magnesian, another result has been the formation of sulphate of magnesia, and beautiful acicular crystals of the Epsom or "hair" salt have here been found. Almost all the "plaster" used in the State comes from the western Helderberg limestones. California is said to have imported from New York in 1868 nearly 25,000 barrels of gypsum.

Long years ago wild stories were told about this mine and its workers; of two strange, taciturn, foreign men who frequented the spot, who kept their mouths shut, and minded their own business in a way astonishing and irritating to the country people around. Nay, more incom¬prehensible, they lived there beneath those silent rocks, and often in dark nights strange lights were seen flashing and moving among the dangerous precipices –wild, heathenish shouts and noises heard among the cavernous recesses of the cliffs. At times in the misty haze of early morning they had been met upon the road with heavy packs upon their sturdy shoulders, wending their way toward some mart, and all who saw them muttered "a good riddance." But suddenly some night lights would again be seen flashing far above the farm-houses among the gloomy, night-hidden rocks. At length they vanished, never to re¬turn. The object of their labors is unknown the ruinous remains of a stone structure resembling a vat, said to be of their construction, yet exists; it is called "The Leach." The mine is known as the "Red-Paint Mine," and it is asserted that the miners were engaged in the manufacture of a red paint from the yellow, ochery oxyd of iron there existing. How they managed it seems now among the lost arts.

Were the Helderberg rock but slightly meta¬morphosed, with here and there a dyke of trap or basalt, what minerals might it not contain? The Almaden mercury mines of Spain (red cinnabar, vermilion, " paint") are in meta¬morphic Silurian limestones. The White Pine and Treasure Hill silver mines of Nevada are in a metamorphosed, crinoidal limestone of the Silurian age, the quartz veins containing the familiar fossils silicified. Old Dutch Colonial Governor Kieft protested that there was gold in this region. Nay, it is said that he found it and doughty Van Der Donck, the historiographer of the New Netherlands, swears to it.

You may reach the cliff top from here by go¬ing further east, where the precipices decrease in height. Search till you find the ascent to a narrow ledge that leads to a square embrasure-like break in the cliff; it seems as though a huge block twenty feet square had been quarried out. In one corner you will discover the crumbling fragments of a tree-ladder; it can not exceed twenty-five feet to the summit. As¬cend, and you will have an idea of the Indian Ladder.

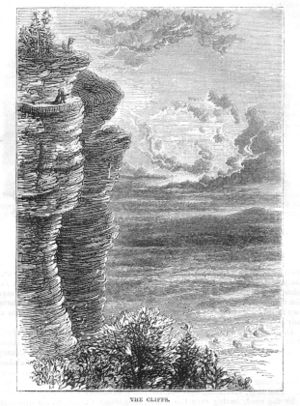

Westward now along the cliff tops, back to¬ward the falls again, and the Indian Ladder road. You reach the stream which forms the Big or Mine Lot Fall, and, stepping through the bushes which obscure your view, stand upon the verge of the precipice. To your left, from the lowest ledge below, the fall leaps the cliff brink, and pours in a steady stream.

Recline here and rest. Six inches beyond your feet is the mossy, weather-worn, blackened cliff edge. A wild flower growing in some cliff below, never once trodden by now living man or beast, raises its unpretending head just above the precipice brink. Out beyond is emp¬ty air; below, the dark afternoon shadows of the perpendicular mountains are already cast¬ing the valley in shade. The wild, rock-filled gorges seem but tiny gutters; the forests shrubbery; all below miniature.

Leaning head and shoulders over as you recline, you see that the rock on which you rest is a projecting shelf but a foot or so in thick¬ness. Should the table-rock yield beneath your weight, rushing with it through mid-air you might light upon the cruel jagged tops of those dead hemlocks, thrust upward from below, whose withered points, lightning-scarred, and broken moss-wreathed limbs, seem waiting, bristling, to receive your fall.

It is grand, thus reclining on the cliff brink, to view the wide-spread landscape to the north of the mountains - the joint basin of the Hudson and the Mohawk - a deep valley more than sixty miles in width. From here you see a wide-spread level country, a true basin, bound¬ed by distant mountain chains; not the bewildering sea of lesser peaks and hills visible from Tahawus. You see, nearest, the deep savage valley, with shades predominating, mountain-walled; the checkered fields and woods beyond, in vast perspective; the distant white farm-house and the red barns, and half forest-hidden steeple of the village church - all vanishing in hazy distance; last, the blue, ragged outline of the northern granite mountains, a bright sky flecked with feathery cirro-cumuli, ever changing, lit with a rich, warm, mellow North American sunlight, brighter than which can not shine either in Italy or on South Sea palm groves.

The cliff, measured by cord and plummet, is here about one hundred and twenty-six feet in height; that of the waterfall may be estimated at one hundred and sixteen feet. Here you may lunch beside the brook, and gaze out past the Hanging Rock, across the valley, to the opposite mountain spur, where a faint ascend¬ing line shows the Indian Ladder road again; by it you will soon descend the mountain. Amidst the bushes back from the falls is a deep, narrow crevice. A stone dropped in rattles and clatters and hops till lost to hearing. To what gloomy cavern is this the sky-light? Some careless person may yet tumble in and learn; yet no one else would ever be the wiser. Such crevices account for the numerous springs at the cliff base. The rock must be ramified with caverns.

Leaving the fall, westward again along the cliff tops, brings you to the Small Fall and a road; following this you come out upon an¬other road. Look to your right: that deep angular cut through the rock is the Pass, the head of the Indian Ladder road.

Descend the defile; you are below the cliffs again in gloomy shadow. Here stood the Indian Ladder. Observe the semi-Alpine character of the road; off this built-up, wharf-like way more than one team has dashed. The trees on the long, steep slope beneath have their history: "The horse struck that one ; the man was found just here."

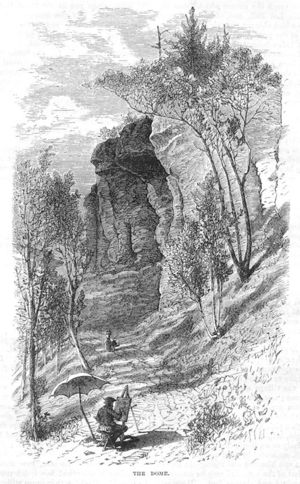

As you descend the road the cliffs increase in height, and the Dome, a mantle-piece-like projection, fairly overhangs and threatens it. Climb the debris beneath the Dome and you will find a path. Follow it. It leads to a cave, the resort of Tories and Indians during the Revolution.

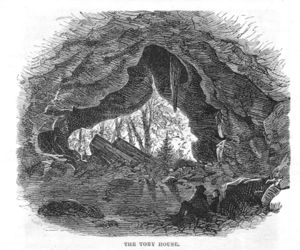

"The Tory House" is a large circular or semicircular cavity in the cliff, just above the road, a good view of which it commands. It is a single room, perhaps twenty-five or thirty feet in diameter, open on one side; looking out over a block of fallen stone - an imperfect rampart - down the wooded slope to the road, and be¬yond, into the deep valley between the mountain spurs.

Here Jacob Salisbury, a notorious royalist spy, is said to have been captured, about the time that Burgoyne was marching his army to¬ward the now historic plains of Saratoga, visible from the mountain-top. The capture of this spy was deemed of considerable importance. It was with difficulty that his lurking-place was discovered and his projects frustrated.

No road then climbed these cliffs. In those wild, unsafe days the wolves were left in undisturbed possession, and the cave was almost unknown. Imagine the darkness of night enveloping the scene. Within the cave, the dusky figure of a man who kneels before a feeble and smoking fire, which ever and anon gives forth a lurid flash - lights for a moment the dungeon-like cave - shines from the brass-bound butts of the huge pistols decorating his belt; then dis¬appears in more mysterious shadow. The thick smoke irritates, he sneezes, how melancholy and hollow is the echo! how quick suppressed the sound! Hark! a twig snaps without; the rattling fall of a stone is heard! The flame leaps up once more as he turns his savage, bearded face; mark the knit brows, the glaring eyes - a desperate spy. His right hand reaches toward his musket, yet he hesitates. A heavy tread outside; the rattling of many stones; a brushing through the bushes. He starts de¬fiantly to his feet; though trembling, cocks his musket - at bay! There is a muttering of hu¬man voices in the impenetrable darkness with¬out ; an ominous clicking as of many rifle-locks ; and suddenly some one cries out, "Jacob Salis¬bury, lay down your arms! You are surrounded and can not escape. A dozen rifles are leveled at your breast." He hesitates.

“Down with your musket !" shouts one with-out. "Do you love treason better than life?" As he dashes his musket, with a curse, to the ground, the flame leaps brightly up and shows the shadowy forms of his foemen; their leveled rifles, steady aim; their leader, sword in hand, in front. Disarmed and bound, the spy is hurried down the mountain, and the lonely cavern abandoned to wild beasts again.

In the roof of the Tory House is a dark, tubular or spire-like cavity, which has, apparently, no connection with any other chamber or cavern. You may, returning, descend the mountain by the road, having seen the more prominent places of interest of the Indian Ladder region.

I will now locate and slightly describe a few of the numberless Helderberg caves. Indeed, without such guidance, the visitor might never find any of them for to discover caves appears to require a cave-hunting instinct, a learned eye. The under-world has its peculiarities. It differs from the upper-world. Its rivers run at right angles beneath the surface torrents, and are generally little influenced by surface storms and changes. Some run a clear, cold, unaltering, constant stream; others ebb and flow with the seasons; are impassable, muddy, furious in spring flood-time ; and the waters vanish, dry up, and are lost in seasons of drought.

The limestone rock of the Helderberg is the cave rock of the world. Other names it may have beyond the oceans; but the rock is of the same age, and contains fossils similar to those found here. Only in Silurian limestones is there space for a region of extensive caves - ¬" Silurian," on this continent, carries Helderberg with it. The Mammoth Cave of Kentucky appears to be in the corniferous, upper Helderberg limestone, which is, however, Devonian. In England, on the Continent, in Palestine, are caverns in limestone, and some in other rock, but rock which has been changed, having by heat been metamorphosed into marbles and the like.

Within thirty miles of the Indian Ladder one may count twenty caverns large and small. Among them, in Schoharie County, Ball's or Gebhard's Cave-brightest of alabaster caverns - whose gloomy portal drops perpendicular over a hundred feet to a region of large lake and wondrous waterfalls; and Howe's or the Otsgaragee Cavern, which strives to rival Kentucky's Mammoth Cave.

The caves of the Helderberg are not glittering crystal grottoes. Though often extensive, they are dark and dungeon-like, damp and muddy; on every side they show the means which made them. The hollow, constant rush¬ing of the water also tells the story of their formation.

Among the cliffs, however, are some caves comparatively or quite dry. Many a dark hole and crevice may be seen on the face of the impregnable precipices; and the water-worn appearance of the rock just below these openings proves them the entrance of unknown caves. None have explored, none save the fool-hardy will explore, their passages.

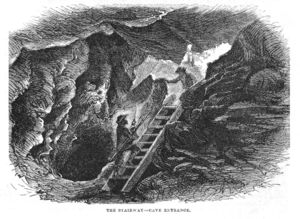

Sutphen's Cave, near the Indian Ladder, reached by descending a narrow crevice through the rock to a ledge a few inches wide. Along this you crawl, the cliff above and below you, a dangerous path in winter, ice and snow covered. Reaching a chill recess beneath overhanging cliffs, you are at the cave entrance. The cave is said to be of some extent, and perhaps it is¬under water. A short distance in, after wading at one place knee-deep, icy cold, the care becomes spacious, and you reach a deep, clear body of water. It is said that in a heavy rain - storm this cave fills up suddenly, and pours a perfect torrent from its mouth. One of those savage, rock-filled gorges descends from this cave's mouth down the water-worn mountain slope.

Westward, among the cliffs, above the village of Knowersville, is Livingston's Cave, a small, dry, and romantic cavern. Should you happen to be near, it is worth a visit. West and east there are many more caves which you may find by seeking. Near the Hudson, toward Coeyman's, there are several.

At Clarksville, twelve miles from Albany, and eight or ten miles southeast from the Indian Ladder, are more caves. Two of these are well known; the entrance of one is in the back-yard of one of the village houses. The subterranean river is the house well; a pair of steps lead down into a crevice in the rock. They have no other water. For drinking it is unsurpassed but it issues from lime rock, and is therefore hard and unfit for washing. This same river bursts forth near by in the bed of the Oniskethau, and aids that stream to run a saw and paper mill. Chaff thrown upon the river in the cave is soon found floating on the mill-pond. The stream empties into the Hudson at Coeyman's. I once heard it remarked that an amphibious animal might make its way through the caverns from Hudson River to Niagara Falls - without once coming forth to daylight!

These two caves are said to be respectively one-eighth and one-half a mile in length. They should not be called two caves, how¬ever, for the "river" seems to flow from one to the other, and forms a connection which a person who likes ice-water baths might explore. Taken as one cave they may exceed a mile in length. The smaller cave is dry and airy, and has some spacious corridors. Squeezing your way down through the narrow entrance you reach a sort of room-the vestibule-faintly lit with the few white rays of daylight which glimmer down through the entrance. You have suddenly passed into a dim region of silence, only broken by the faint tinkling and murmuring of the subterranean stream below. You light your lanterns, and the red flame guides your footsteps. A short way through a narrow passage and you ascend into a lofty chamber-the "Room of the Gallery." Should you visit it in winter, as I once did, you may start horrified back. Two or three ghostly, white columns rise here and there from the floor! There are no such stalagmites in this cave. What, then, are these white columns gathered in a spectral circle? You approach; they move not. Nearer, nearer still, and the white columns resolve themselves into fantastic stalagmites of ice-beautiful yet fragile. The water dropping from the roof, the frost which reaches in thus far, account for them.

That dark hole plunging downward to the right is the continuation of the cave; descend, and turn in at and climb the first side passage to your left, and you will reach the "Gallery."

It is related that a villager, venturing in to pass a hot summer night, having but a solitary tallow-candle, his light became extinguished, and he thought himself all but lost. Feeling along in the dark to find some means of exit, he was suddenly precipitated into a dark pit. A while after, as he sought to ascend, he fell again, deeper, receiving severe injuries. Dread-fully alarmed, he rushed hither and thither, only to fall a third time, and still deeper. He swooned from terror; and when he awoke he observed a faint light opposite. Scrambling toward it, he entered a room; it was the cave entrance! Some assert that he mistook the passage in returning, and merely climbed to and fell from the gallery - three several times.

There are other large rooms and corridors in this cave, but there are few stalactites or stalagmites, if any. In one place are some beautiful incrustations of spar and in another spot a vein of the massive calc-spar, with large crystals, is found. The latter sometimes contains the Silurian anthracite, supposed to have had its origin in the organic animal life of that age. The rock inclosing the calc-spar is a granular or sub-crystalline limestone-the Upper Helderberg.

A singular feature of the cave are the water¬worn pot-holes in the rock ceiling. Every one knows that rational, common-sense brooks or rivers of the surface world make them according to law of gravitation in their water-worn beds. Here natural laws seem laughed to scorn; and these pot-holes, as though from very perverseness, are set inverted in the roof. They were formed undoubtedly when the cave was filled with water, whirling and rushing against the roof.

A narrow passage leads to the extremity of the cave. Where it enlarges is a steep and rather slippery descent to water. This is called by some a lake; the rock roof comes so close to the surface that its lateral extent can not be seen. Naptha poured upon the water and ig¬nited, though it makes a singular sight, burning with a blue, lambent flame, shows nothing, and the darkness is deeper when it dies away. The water is very clear and still, and increases in depth, gradually, off the shore. There are here no "eyeless fishes."

The "Half-mile Cave"-the larger cave, or the longer end of the cave, if they are but one - is about a quarter of a mile from the hotel in Clarksville. This cave is often visited, and has a large, wooden, cellar-like door, and wet, slippery steps, which lead in winter down into warm, steaming darkness.

Mind your steps; I speak literally. Now go down the dark hole on your right; it is a steep descent. You are in darkness again, and your lights but feebly illuminate the place. There is a sickening damp warmth; it is not unlike a charnel-house, a catacomb. This mouldy earth beneath your feet, lixiviated, would prob¬ably yield much nitre; the earth of caves generally contains it. Notice those black strata veins of flinty hornstone; they may have served their time in the days of flint-lock rifles. Here is flint, there saltpeter; pyrites through heat will yield sulphur; the alders and willows from beside mountain brooks give choice charcoal. Here is gunpowder in the raw, for those adepts in its manufacture!

It was these veins of brittle, translucent flint, called hornstone, which gave the name of "corniferous limestone" to this rock, from the Latin cornu-horn. It was not the fossil shell, the cow-horn shaped zaphrentis, which originated the name though that is the most prominent of the many brown, weathered shells incrusting the roof and walls of the cave. These same shells-zaphrentis-project similarly from the walls of the great Kentucky cavern. This corniferous (upper Helderberg) limestone is peculiar as being the oldest rock in which the fossil remains of fishes have been found.

You may have a mile or more of clambering in and out from this cave, and that is as good, though not quite so bad, as twenty-five miles. There are long passages where you might drive a team of horses and a wagon; narrow, muddy passages in profusion; bats, overhead and flut¬tering past you, every where.

The bats bang from the ceilings separately, and from one another in curious festoons. They are now hibernating. Aroused by your ap¬proach, some take wing and occasionally strike against your lantern, shattering the glass. On all sides you hear them squeaking and chatter-ing and grinding with their teeth; it is horrid. How they live there is a mystery; no suitable food is visible, and the door of the cavern is kept closed. Some of the bats seem withered and half dead ; others are more lively. The gray or frosty bat is sometimes found here. The cheiroptera of this cave have been described in Goodman's "Natural History;" for this is the one therein mentioned as "an extensive cavern about twelve miles south of Albany, New York." They have quite changed their habits since sketches were made of them by that reliable naturalist. In his time, it is evident from the engravings, all bats hung themselves cozily head up; now the contrary vampires all hang head down, in a way that could not fail to be alarming to apoplectics - a vile rebellion against the naturalist. Bats, sleeping, hang then with their heads downward, holding fast by the little paws they have behind, and not by the hooks attached to their membranous wings. In their flight near the roof they stop and flutter for a mo¬ment, then hang correctly. It is thought that they catch by their hooks, and, if the place suit them, assume the upside-down posture. If they fall to the ground they are for the while help¬less; however, with the aid of their front hooks, they climb to some little eminence from which, by turning a sort of somersault, they fall down, and, as they fall, take wing and search for bet¬ter quarters. Nature has given them instinct so to repose that, when disturbed, they may be able to take to flight and escape.

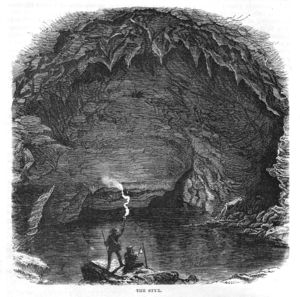

If you determine to see the end of the cave and the lake, and are not afraid of mud and low, flat passages, you will go further, perhaps fare worse. Again the cavern enlarges, a black emptiness is before you. Approach. You stand upon the shores of "Styx." A vaulted roof of dripping rock, a silent, echoing cavity, scarcely illuminated by dim lantern-light. Un¬ruffled are the still, deep waters, green, though clear. The silence only broken by the sudden, occasional tinkling of a drop of water falling somewhere in one of the dark side passages, only to be explored in a boat. The boat is wrecked.

In returning you have to repeat the crawling and scrambling through the low, narrow, or wet and muddy passages: it seems endless. You halt to await the approach of a loitering companion. His lantern is seen, in distant per¬spective, far down the dark corridor. You shout for him to hurry. Hark to the distant, echoing answer, "Coming!" Turn your lan¬tern this way, and look down the long, shadowy passage of the cavern; in the dim vista he seems an imp, dancing along with a fire-brand. Suddenly, while you think him yet at a dis¬tance, he seems to enlarge, and is close to you.

I once fired a pistol-shot in this cave to bear the echoes; instead of the sharp crack which should have followed the flash came a volley of deep, echoing, hollow thunders, a rolling and swelling roar, a musical, harmonious earth¬quake, deafening. One of our party who was on ahead took it for heavy, celestial thunder¬ing.

Cave explorations are interesting to those who love to see the wonders of nature-things be-fore unseen, new and surprising. Who knows, some one this exploring may discover a great, subterranean, transcontinental river; an underground, round-the-world canal, cheapening freightage between New York and San Francisco. Whether you should find this wondrous stream or not, a visit to the under-world will not be forgotten ; the hornstone and the fossils collected, nay, the grimy, shattered lantern that you carried, will ever remain objects of interest.

Winter is the best time to visit caves; it is certainly the most healthy season, for it is dangerous to enter a cold, damp cave in hot weather. Nevertheless, ice closes the entrance of some caves in winter, and, if among the cliffs, the climbing is dangerous.

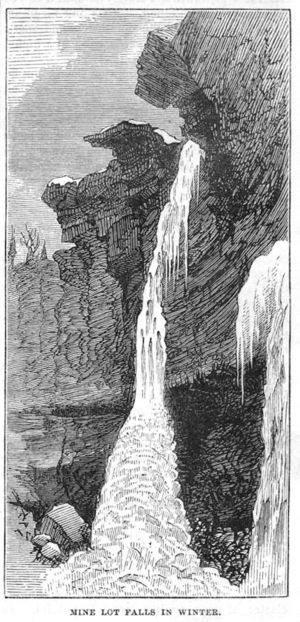

In winter the Indian Ladder or Mine Lot Fall is one huge icicle from the cliff brink to its base; the water pours down - an unceasing stream - through the huge frost-proof conduit it has formed for itself. A pyramid of pure green-white ice, glittering, resplendent with icicles, which in fringed sheets, strange and fantastic shapes, adorn the translucent column, one hundred and sixteen feet in height. Have a care how you climb up among the rocks in winter; it is almost impossible to descend again, and dread indeed is the ascent. Upward may prove your only path to safety over slippery ice and snow-capped rocks; below you the cliff, the tree-tops, the dread craggy-mountain slope! Hands icy and stiffened, useless and bleeding, my only reward for the climb depicted was a bit of rare moss (the Hamelia gracilis) which I found on the rock above.

Frequently upon the brow of the mountain you will see a ruined tower perched; surprised, you draw near. The door is low and narrow, and seems to be almost closed by the debris; it has a very ancient look, and resembles some old feudal watch-tower you may have seen in Europe. The slope below is white with rub¬bish, and covered with fallen stone - the tower itself blackened with fire. It is a Helderberg lime-kiln. The lime made here is the best known; many of the poorer farmers burn lime in the winter. It replaces the charcoal burning of other regions, and though quite as laborious and scorching, is more remunerative. The fuel used is wood, and the great heaps of ashes thus obtained are greedily sought by agriculturists and potash makers. The kilns are of refractory rock; blocks of clay-slate are preferred; and they are generally built near the quarry where the limestone is blasted out. These lime- burners will tell you curious stories of the "animals" they have seen in the rocks; some of them have singular collections of the fossils.

The limestone, when blasted, breaks into large, regular blocks, well suited for building purposes. This is generally owing to the cleavage, but frequently huge blocks are quarried which are perfectly loose and need no blasting. These owe their origin to "shrinkage clefts," which, as another singular feature of Helderberg scenery, is worth explanation.

Often the roads on the summit of Helderberg are of solid, level rock; the mountain top is a plateau as smooth as a table. Canter¬ing along on horseback the constant ringing clatter of iron against stone is painful. In places the rock is jointed and in small blocks, and resembles a Belgian pavement; again it changes, and a singular sight meets your eyes.

The rock plateau is split by numberless parallel crevices, stretching on either side in perspective; if you view them with half-closed eyes the dark clefts resemble railroad tracks. The sutures between the long blocks or trunks of stone are often twenty feet or more in depth, though sometimes choked with rubbish, and generally six, eight, or ten inches wide. In storms the water rushes down into the caves below. On the mountain (above the village of New Salem) these clefts extend perfectly parallel for miles. At times rectangular or diagonal sutures cross the main ones then the rock is cut in blocks a yard square on the surface; downward-twenty feet, more or less-it is a pillar you may teeter it where it is; a thousand like you could not lift it out. These barren, arid rocks refuse to grow aught save stunted cedars, ground-hemlocks, and white birches, though now and then a larger kind of tree supports itself in a rock cleft. The foxes also find excellent hiding-places in these clefts.

Near Clarksville, on the slope of Copeland Hill, the clefts are two, three, or four feet wide; sometimes black, bottomless looking pits, unexplored. Below are often other subterraneous rivers, flowing no one knows where from or whither. A robber once had a boat there, and in a cavern deposited stolen goods; his secret was discovered, and himself and plunder captured. The sudden and mysterious disappearance of obnoxious men is mentioned in connection with these dark pits. There is a stream which dashes, full-bodied, into a great pit or sink-hole in the rock, travels an unknown course, and issues at once from a cliff three quarters of a mile distant.

The slippery or red elm (Ulinus fulva) is, or used to be, very abundant, and tons of the bark have from hence been brought to market. Maple-sugar making is another industry common here. In frosty spring, smoke rising here and there over the woods tells of the fires crackling and flaming under the great iron kettles in the open forest, or-as at old Peter Ball's, near Berne, on the slope of Mount Uhi-in well-built sap-house. In early frosty mornings the "Sugar Bush" is a bright scene the sunlight streams down over the mountain, and the old trees cast long shadows. The sugar-maker hurries hither and thither, collecting the buck¬ets of clear, colorless sap, throwing out the ice which has frozen on the surface overnight (for experience has taught him that in freezing it has lost its sugar), placing empty buckets under the taps-ever busy.

But there is not space to mention every thing of interest in this forgotten range of hills-the numerous waterfalls and caverns and mountain- split gulfs.

If but a few learn from these scant notes that there is something new to be seen at home as well as abroad I am satisfied.

Harper’s October 1869