Sesquicentennial History Article

From the booklet, Booklet, Knox, New York Sesquicentennial, 1822-1972, Mrs. Frieda Saddlemire, Chairman - Used with permission from the Knox Historical Society

In The Beginning ...

The Town of Knox, which contains the hamlets of Knox and Township, embraces an area of approximately 26,000 acres wedged into the northeastern corner of Albany County. At the time of the 1970 census, a population of 1,819 lived beyond the wall of the Helderberg escarpment, among the hills and valleys of the glaciated plateau that is drained by the Bozenkill and the Beaverdam, within the boundaries of the Township. In 1845, a population of 2,145 was reported and the village of Knoxville, as it was then known, contained some 30 dwellings.

Prior to 1790, the then nameless township was known only as a wild, mountainous part of the West Manor of Rensselaerwyck. At that time, Watervliet, the "mother" of the towns of Albany County, was a vast area with indefinite boundaries. As the population increased, it became necessary to reduce the sprawling area into administrative units of manageable size. In 1790, Rensselaerville, which included the present townships of Berne, Westerlo,. and Knox, was separated from the "mother" town. In 1795, Berne, which included the territory now known as Knox, was apportioned from Rensselaerville. Finally, on February 28, 1822, the town of Knox was set off from Berne and entered into history as a separate township.

The origin of the name of the township, and of its principal village, has not been fully resolved. Tenney and Howell (History of the County of Albany, N. Y., from 1609 to 1886, compiled by George Rogers Howell and Jonathan Tenney and "assisted by local writers" (New York, 1886)) assert that the name derives from the Revolutionary War hero, Colonel Knox. However, Hamilton Child's 1870 Gazetteer of the Towns of Albany states that Knox was named in honor of John Knox, the Reformer. Senior citizens of the township favor the Tenney and Howell version.

The village was once called "Pucker Street". and that name is still remembered by many residents. The people of Pucker Street were reputed to be very "stuck up", and aloof. One resident recalls that "when they rode through the village, they held up their heads so high!" According to this version, the vinegary attitudes of the inhabitants of Pucker Street inspired the colloquial name. An alternate version would have it that the nickname was pinned onto the village by young men of the day because so many old maids lived there — presumably of sour miens and dispositions.

Still another vernacular name was recorded by the Knowersville Enterprise (the present Altamont Enterprise) in 1884: "... the village lay near the centre of the town and the street was nearly 100 feet wide so it is known as the "Street."

Finally, an even earlier name for the site of the village is reported by Tenney and Howell. According to this legend, a small party of pioneers, led by an Indian guide, encamped on the site of the future village of Knox. where a bitter dispute arose over the question of the group's leadership. One version has it that the contending parties resolved their differences and continued on to Schoharie. Tenney and Howell. however, relate that the party divided into three factions, one of which went on to Schoharie, while another set off for Berne, and the third remained at the site of Knox. Therefore, according to the legend, the area where the divisive quarrel took place became known as Fechtburg, or Fighting Hill.

A map of the west part of the Manor of Rensselaerwyck, prepared in 1787 by Wm. Cockburn for Stephen Van Rensselaer, shows land divided into distinct plots of 120 acres or less. A reproduction of this map can be seen at the Knox Fire House. It is evident, therefore, that many settlers were already on the land when the map was prepared. Historians conclude that these early settlers were lease-holders, but this cannot now he documented conclusively, because the original leases were among the Van Rensselaer papers destroyed in the Capital fire.

Some of those early names, spelled as they appear on the 1787 map, are: Haverleigh, Klikeman, Ouderkerk, Secor, Styner, Zant, Zee, Seidelmeyer, Shultis, Quay, Truax, Werner, Miller, Bedstead, Shoemaker, Berkley, Shafer, Basler, Angle, Kneiskern, Zimmer. Chesbrough, Cosbert, Wykerver.

Around 1790, following the Revolutionary War, many settlers came into the area from the vicinity of Stonington. Connecticut, and among the names which then appeared in the ledger books are: Abbot, Brown. Whipple, Todd, Dennison, Cary, Gallup, Frink, Taber, Coates, Batcher, Williams, and Baxter.

The patroon system, which was exported to the New World from Holland long after it had been abandoned there, encumbered a section of the Hudson River valley and the adjacent lands on either side with a coercive aristocracy that led to long, bitter years of hardship and suffering, and eventually to armed revolt.

In 1629, Kiliaen Van Rensselaer. a pearl and diamond merchant of Amsterdam. and a director of the Dutch West India Company, was given a charter for a grant of land in America in return for his agreement to establish a colony of fifty persons on the grant within four years. Kiliaen's grant rapidly became the Manor of Rensselaerwyck, which stretched along both sides of the Hudson river for 24 miles and encompassed an area of about 700 thousand acres.

The first patroon of Rensselaerwyck never saw or visited his estate, but his agents served him well. The vast tract was handed down to his descendants intact, and became a hereditary seat of enormous economic and political power, as well as a source of ever-increasing wealth. The manor survived both the British conquest of the colonies in 1664 and the American Revolution more than a century later, with the powers of the patroon only superficially diminished.

Henry Christman's Tin Horns and Calico, a stirring and authoritative account of the struggle of the reluctant tenant farmers against entrenched injustice, describes their situation in the 1830's:

“Under the patroon system, flourishing as vigorously as it had in the days of the early seventeenth century, a few families, intricately intermarried, controlled the destinies of three hundred thousand people and ruled in almost kingly splendor over nearly two million acres of land.”

Stephen Van Rensselaer III, sixth lord of the manor, and his son, Stephen IV, were the descendants of old Kiliaen most intimately bound up with the history of Knox. In Tin Horns and Calico, Henry Christman portrays the state of the manor as it was when Stephen Ill came of age in 1785:

“... Only scattered settlers had gone beyond the fertile valley lands to clear the heights of the Helderbergs, where thousands of untouched acres still awaited the ax and the plow. Stephen now announced a ‘liberal’' program to people the rest of his seven hundred thousand acres. He would give the patriots of the Revolution homesteads without cost; only after the farms became productive would he ask any compensation.”

“Surveyors were sent over the hills; farms of one hundred and twenty acres each were blocked out; exaggerated reports were issued about the fertility of the soil... Men began to come and to each the patroon said: ‘Go and find you a situation. You may occupy it for seven years free. Then come in at the office, and I will give you a durable lease with a moderate wheat rent.’”

Several thousand farms were taken up on the basis of the patroon's vague offer, and for most of the prospective lease-holders, especially for those who found their "situations" in the rocky uplands of the Helderbergs, the seven years spent in clearing a homestead in the wilderness, were years of cruel privation and rugged toil. As Henry Christman wrote:

“Here the farmers spent their energy wresting a living from the grudging land, and talked with patient humor of the stones that pushed up perennially as the only dependable crop. Some even fancied that the Helderbergs were the last place made by God, and the dumping-ground for all the rock left over from Creation.”

Many settlers had to "hire out" in order to support their families while they cleared their farms. Some traveled many miles to work for a half-bushel of corn a day, trudged home with the corn on their backs, and then picked up their axes to work at their own homesteads.

When the seven years of unremitting labor had ended and the settlers went back to the patroon for their "durable leases, “they were handed contracts of "incomplete sale,” which had been drafted for the patroon by his brother-in-law, Alexander Hamilton. With these “leases,” or “incomplete sale” contracts, the patroon evaded the intent of laws enacted in 1792, and “sold” to the settlers the lands which they had cleared, subject to certain conditions, as set forth in Tin Horns and Calico:

“As ‘'purchase’ price for the title to and the use of the soil, the tenant was to pay ten to fourteen bushels of winter wheat annually, and four fat fowls; and he was to give one day's service each year with team and wagon. He was to pay all taxes, and was to use the land for agricultural purposes only. The patroon specifically reserved to himself all wood, mineral and water rights, and the right of re-entry to exploit these resources. The tenant could not sell the property, but only his contract of incomplete sale, with its terms unaltered. A ‘quarter-sale’ clause restricted him still further: if he wished to sell, the landlord had the option of collecting one-fourth of the sale price or recovering full title to the property at three-quarters of the market price. Thus the landlord kept for himself all the advantages of landownership, while saddling the ‘tenant’ with all the obligations, such as taxes and road-building.”

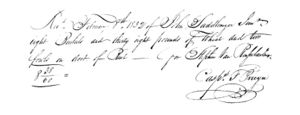

Rent was due on the first of January. All through the Helderbergs teams were hitched to wagons or sleighs for the long pull over frozen roads to the office of the distant patroon. Some farmers traveled for more than a day. Once they had reached the office of the patroon's agent, they waited outside in the cold yard until their names were called. When summoned, they went up to a small, circular window and handed their “rates” to the agent inside. In turn, each tenant who had met his obligation came away from the window clutching his receipt for wheat and “four fat fowls” which had been delivered previously to one of the patroon's collection points. But whether a tenant could pay or not, or whether he was sick or injured, he was required to be represented at the patroon's office on Rent Day. And no tenant was allowed inside the office, or permitted to examine the books in which his rents were recorded.

The weary tenant turned away from the patroon's window with only his receipt and the agent's assurance that the entries were correct. But these two things, a bit of paper and perhaps a curt word, were a heavy burden on his mind during the long journey back to a farm in the hills.