Becker, Helen Elizabeth

Birth

Education

Occupation

Marriage & Children

Death

Obituary

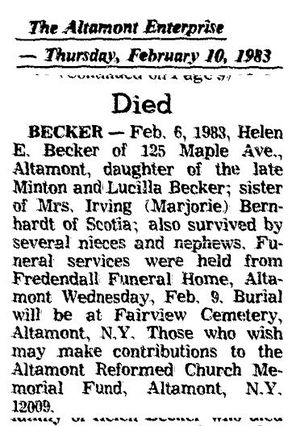

Died

BECKER —Feb, 6,1983, Helen E. Becker of 125 Maple Ave,, Altamont, daughter of the late Minton and'Lucilla Becker; sister of Mrs, Irving (Marjorie) Bernhardt of Scotia; also survived by several nieces and nephews. Funeral services were held from Fredendall Funeral Home, Altamont Wednesday, Feb, 9, Burial will be at Fairview Cemetery, Altamont, N.Y. Those who wish may make contributions to the Altamont Reformed Church Memorial Fund, Altamont, N.Y. 12009.

- Altamont Enterprise — February 10, 1983

Additional Media

Helen Becker: A Personal Memoir

By CAROL DuBRIN

What does one say with the passing of an era — an era that ends when one special person dies? Such it is now in Altamont with the death Sunday of our neighbor and friend, Helen BecKer. Known to all of us, a friend to village children through many years, Helen's departure will leave avoid no other can fill.

Minton Becker had a harness and shoe repair shop on Maple Avenue in Altamont always, it seems. My (generation and at least several of those before mine grew up knowing that was where to go if one needed any type of leather goods repaired. And though she lived home and helped her mother, Lucilla, early on Helen, a father's girl and avowed tom-boy, took an interest in the shop.

Not that she didn't have her turn at more "womanly" things, hiring out to cook and clean. Fiercely independent, she just liked working with her father better — or being (out in a garden growing things.

Friends for many years she and I have often reminisced over our doings and present. I've heard tales of the mountains of food cooked up to feed the harvesters at the Wade Swartz farm, "Amy always fed them plenty," and she'd describe platters of pork chops, bowls of potatoes and pies of every description she's helped produce.

Or the times cleaning for Miss Peters, dusting all her antiques and around her many collections. Miss Peters' fantastic gardens were a special joy and inspiration.

All this work was to a special end — it meant money carefully saved until finally she could buy her own car and earn "freedom," Not freedom from her home or her community — just the means to "go."

Go might mean taking a church youth group or Sunday school class on a picnic or taking some elderly shutins for a drive or a friend to the city or, best of all, being able to go visit some relative in another state. Helen took her pleasures in simple things.

As Minton Becker had gotten older and needed help, Helen spent more and more time with him, learning by doing, repairing the occasional harness and working on shoes. She learned how to use all the sturdy old equipment in the place, (It is still all there and has been in use until the past few weeks.)

The Becker shop occupied a lengthwise hall of the first floor of 125 Maple Ave. I remember taking dancing lessons in the long, narrow room in the other side of the building. Helen told me that at one time the basement was a fish market and the reason her garden grew so well out back was all the fish heads and entrails buried in various garbage holes there.

Arthur Gregg, former town historian, recalled a period before that when it was a taproom. The building was apparently higher at one time and had been lowered on a new foundation.

Altamont seems to have been great on moving and changing old buildings so that what is now an apartment house on Maple Ave. was once a school on Lincoln Ave. (School St.) The shed garage behind the apartments next to Helen's shop were once part of the horse sheds behind the Reformed Church, attached to the barn still there — for parishioners' horses during services. Even they had been moved there from their first site behind the original Reformed Church located about where Junction Hardware is now.

This practical, saving nature of the community was a part of Helen, too.

"Waste not, want not" found her constantly recycling things and when she took over her father's business there always was a corner for used clothing, shoes, skates and such for resale. I kept up with my children's growing feet with ice skates from that shop, returning outgrown ones for someone else's use.

Did you need sewing findings or perhaps a greeting card? Helen carried those, too. And somewhere along the line Helen brought candy into the store.

In an old-fashioned glass display case were quantities of penny candies. Children could go out with a great handful for a nickel.

My friend Charlie Gage recalls the great bargains he and his buddies always found to satisfy their sweet tooth— and that was 35 years ago. Certainly my children as a treat or for being "good;" were rewarded with pennies so they could go to Helen's shop and choose anything they wanted.

Helen would wait patiently while young shoppers tried to make up their minds, explaining that these were two for a penny or those five for that single cent. Then she'd put their choices in a little brown paper bag that the kids would come out gripping tightly.

Certain changes came with time— plastic baggies and fewer candies for that penny. But she always kept some that could be bought at that price. We suspected she sold them at a loss.

As Millie Plummer said to me, "Helen never saw a bad kid." She might see youngsters with problems, but she loved them all, tried to help them all; And she would appeal to those who she thought might help one of "her kids." I recall telephone calls about doctors or clothing.

Helen was fast to help others, oo. If ladies wished^ to earn a bit of money by their handiwork, Helen would find display case space for it and sell it—keeping that money in a separate box or can, rarely keeping any commission for herself. Her shop became a recycling station for church groups collecting cans, bottles and papers.

She carried farm produce for local farmers, sold berries for industrious kids and bunches of bright bittersweet collected along the fencerows. And flowers from her own garden, too, though more often she would give them away.

Her produce became such a popular item that with the help of the Abbruzzese family of Altamont Orchards, she got stuff from the farmers market to resell very reasonably in her shop. She always donated the potatoes or squash for church dinners and each Christmas gave individually packed bags or boxes of candy for Santa to distribute to all the children at the Sunday school party. In later years, the church took her under its wing in appreciation.

Perhaps the candy store was an outgrowth of Helen's own love of sweets. Anyway, along the line she developed diabetes and many trials lay ahead of her.

Stubborn, she would admit to no problems. So she ignored them. And as with all ignored problems it was at her own peril.

She lost one leg to diabetes after a long fight with gangrenous sores on her heel. She accepted it matter-of-factly but found that she didn't like her artificial leg much. Still, she conducted business as usual on crutches as soon as she could get back to her shop and home. (The side of the building where I had taken those dancing classes was her apartment.)

Conceding nothing except her precious car (she gave it to her nephew) and trying to cook with sugar substitutes, Helen kept up her gardens (with the help of the Miller boys), with her housekeeping, canning and preserving in addition to her shop work.

Then I remember one long, hot summer when we fought with bed rest, special dressings and diets. But again the dread diabetes took its toll. She lost her remaining leg. Lesser souls would have been completely devastated. But, refusing two artificial legs — "I'd break my neck, too" — she went back to her home and shop again where friends had altered things enough to accommodate a wheelchair.

Along about then, Mary Maslowsky came upon the scene and she became Helen' "legs" — kneeling in the garden to keep the flowers, the strawberries, the vegetables coming, shopping, picking up the mail, banking, pushing the wheelchair on "outings" around the village (usually stopping at the Penguin for refreshment along the way.

They even entered a walk-a-thon or two until Mary's own health precluded that. Other Mends helped, but Mary was the mainstay. She even learned to use that antique shoe repair equipment in the shop under Helen's direction, 1 don't believe Helen ever realized how much she depended on Mary as she continued on her defiantly independent way. She told me it was her "Indian blood" and proudly proclaimed an Indian grandmother somewhere along the line. Visiting a western Indian reservation, I brought her back a tiny piece of scrimshaw (Indian artwork incised on elk horn) on a chain whichIputaroundher neck. She loved it—it gave her a reason to tell about her own "Indian connection," Julia Drebitko had come into our village life, living right across the street from Helen, And they becamefriends, Jwlia alwayshad a hearty smile _...** laugh to share and made sure to visit Helen daily —especiallyif Helen was "Down," There were those days — pain in her "legs and feet" were genuine, the brain's response to cold or atmospheric changes, and the diabetes dimmed the eyes (Helen usedmagnifyinggoggles to work), Julia's daily round usually included picking up milk or some other small item at the store for Helen, But then came theday a few weeks ago when Julia was felledtey a heart attack. And with her passing Helen seemed to have lost her own spirit. And despite encouragement from her sister, Marjorie, and her many friends, Helen gave up the long fight. The Lord called her home, Helen Becker, Oct. 14, 1913 — Feb. 6,1983. One of a kind. There are no others.

Helen Becker Memoir -Altamont Enterprise — February 10, 1983 Helen Becker Memoir -Altamont Enterprise — February 10, 1983

Sources