Difference between revisions of "Bradley, Joseph P."

JElberfeld (talk | contribs) m |

JElberfeld (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==Marriage & Children== <!--DELETE THIS LINE IF NOT NEEDED--> | ==Marriage & Children== <!--DELETE THIS LINE IF NOT NEEDED--> | ||

| − | He married Mary Hornblower in Newark in 1844.<ref name="wiki">from his biography in [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Philo_Bradley Wikipedia]</ref> His ancestors, children, and descendants are in the Hilltowns Genealogy posted on the [[Berne Historical Project]] web site. | + | He married Mary Hornblower in Newark in 1844.<ref name="wiki">from his biography in [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Philo_Bradley Wikipedia]</ref> His ancestors, children, and descendants are in the Hilltowns Genealogy posted on the [[b:Berne Historical Project|Berne Historical Project]] web site. |

==Occupation== <!--DELETE THIS LINE IF NOT NEEDED--> | ==Occupation== <!--DELETE THIS LINE IF NOT NEEDED--> | ||

Revision as of 22:18, 2 March 2013

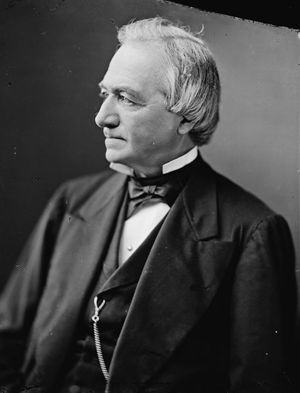

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection

Birth

Joseph P. Bradley was born to humble beginnings on a farm on Cole Hill in Berne on March 14, 1813 son of Philo Bradley and Mercy Gardiner.[1]

Education

Bradley attended local schools. He began teaching at the age of 16. In 1833, the Dutch Reformed Church of Berne advanced young Joseph Bradley $250 to study for the ministry at Rutgers University, graduating in 1836. After graduation he was made Principal of the Millstone Academy. Not long afterward, he was persuaded by his Rutgers classmate Frederick T. Frelinghuysen to join him in Newark and pursue legal studies at the Office of the Collector of the Port of Newark. He was admitted to the bar in 1839.[2]

Marriage & Children

He married Mary Hornblower in Newark in 1844.[2] His ancestors, children, and descendants are in the Hilltowns Genealogy posted on the Berne Historical Project web site.

Occupation

Bradley's private practice in New Jersey, specializing in patent and railroad law made him very prominent in these fields and quite wealthy. As a commercial litigator, Bradley argued many cases before various federal courts, earning him a national reputation. Thus, in 1870 when a new seat was created on the U.S. Supreme Court, he was sufficiently well known by associates of President Grant to be recommended as a Supreme Court nominee. He authored the majority opinion in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 . Bradley's personal, legal, and court papers are archived at the New Jersey Historical Society in Newark and open for research. Bradley also wrote the opinion in Hans v. Louisiana, holding that a state could not be sued in a federal court by one of its own citizens.

Joseph P. Bradley was an American jurist best known for his service on the United States Supreme Court, and on the Electoral Commission that decided the disputed 1876 presidential election.[2]

Appointment to the Supreme Court

As a commercial litigator, Bradley argued many cases before various federal courts, earning him a national reputation. Thus, in 1870 when a new seat was created on the United States Supreme Court, he was sufficiently well known by associates of President Ulysses S. Grant to be recommended as a Supreme Court nominee. Bradley was nominated on February 7 and was confirmed by the Senate on March 21, taking his seat on the court as an Associate Justice that same day. On moving to Washington, Bradley purchased the home that had previously belonged to Stephen A. Douglas.[2]

Supreme Court Jurisprudence

Bradley took a broad view of the national government's powers under the Commerce Clause but interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution somewhat narrowly, as did much of the rest of the court at the time. He authored the majority opinion in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 but was among the four dissenters in the Slaughterhouse Cases in 1873. His interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment in both cases remained the basis for subsequent rulings through the modern era.

It was due to his intervention that prisoners charged in the Colfax Riot (also known as the Colfax Massacre of 1873) were freed after he happened to attend their trial and ruled that the federal law they were charged under was unconstitutional. This resulted in the federal government's bringing the case on appeal to the Supreme Court as United States v. Cruikshank (1875). The court's ruling on this case meant that the federal government would not intervene on paramilitary and group attacks on individuals. It essentially opened the door to heightened paramilitary activity in the South that forced Republicans from office, suppressed black voting, and opened the way for white Democratic takeover of state legislatures, and resulting Jim Crow legislation and passage of disfranchising constitutions.

Bradley dissented in Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad v. Minnesota, which though not racially motivated was another due process case arising from the Fourteenth Amendment. In his dissent, Bradley argued that the majority had in siding with the railroad created a situation where the reasonableness of an act of a state legislature was a judicial question, subjugating the legislature to the will of the judiciary. Bradley's opinion in this case is echoed in modern arguments regarding judicial activism.

Bradley also wrote the opinion in Hans v. Louisiana, holding that a state could not be sued in a United States federal court by one of its own citizens.

As an individual Supreme Court Justice, Bradley decided In re Guiteau, a petition for habeas corpus filed on behalf of Charles Guiteau, the assassin of President James A. Garfield. Guiteau's lawyers argued that he had been improperly tried in the District of Columbia because, although Guiteau shot Garfield in Washington, D.C., Garfield died at his home in New Jersey. Bradley denied the petition in a lengthy opinion and Guiteau was executed.[2]

1876 Electoral Commission controversy

Bradley is best remembered as being the 15th and final member of the United States Electoral Commission that decided the disputed 1876 presidential election between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden.

A Republican since the early days of the party, Bradley was not an obvious first choice. The four justices charged with selecting the fifth and final justice (who, all realized, would be the deciding vote on the commission as all 14 other members were strictly partisan) initially chose David Davis for the job, but as Davis had just been elected to the United States Senate he was unable to join. The justices then settled on Bradley. The reasons for this are not entirely clear, though it is evident that Bradley was thought by his colleagues to be the most politically neutral; the court overall at that time had more Republicans than Democrats, however.

Bradley wrote a number of opinions on the electoral commission and justified his votes to his own satisfaction; he sided with the Republicans on every case. On the night before the final vote the Democrats visited Dr. Bradley and believed they had convinced him so that he would decide in their favor. But the next morning his vote was pro-Republican and Hayes was declared President. Sometime after midnight, a delegation of Republicans had allegedly visited the Bradley home and perhaps with the aid of Mrs. Bradley, had convinced the Judge to change his opinion. Whatever happened, the vote of Joseph Bradley had elected Rutherford B. Hayes as President of the United States. Because of this he was vilified in the press and privately as well, even receiving a number of death threats at his home in Washington.[2]

Death

Bradley remained on the bench until 1891, when he became greatly weakened by disease (possibly tuberculosis). He took his seat on the bench in October of that year, but was forced to retire a few weeks later by failing health. He died a few months later on January 22, 1892 in Washington, D.C. and was interred at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Newark.[2]

Obituary

Additional Media

Sources